This article is part two of an exploration of yoga and self-leadership to pair with the series I’m currently teaching. If you like this article, consider joining the class; they’re all pay what you can ($0-$25).

In the previous article, I introduced the theme of self-leadership and dug into the idea of self-awareness from an emotional intelligence lens and how it can often be misused as a framework that helps to uphold oppression. The point of that discussion was to distinguish that frame of self-awareness from what I am exploring as Self awareness, informed by the Sri Swami Satchidananda translation and commentary of Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras.

To turn to Self awareness then, I mean deep interrogation and observation of our internal thought processes, emotional reactions, and behaviors. This includes noticing when we do things that we consider ‘good’ and when we do things that we consider ‘bad’ and working with the question of where that opinion came from, whether it’s true, and what the impact is of considering that behavior in yourself as good or bad. This is the groundwork for understanding how we interpret those behaviors or thoughts in others, which can reveal our implicit biases and highlight where we promote and reinforce ideological, interpersonal, institutional, and internalized oppressions.

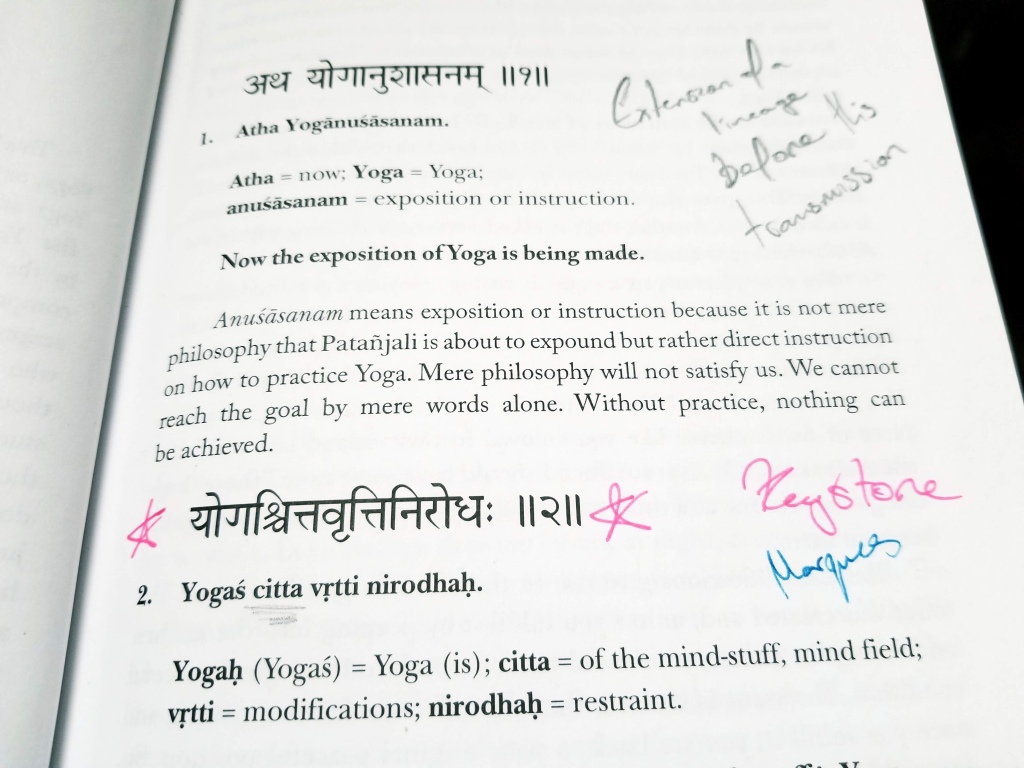

Working with self-awareness this way is rooted early in Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras. The translations below come from the Sri Swami Satchidananda commentary. I’ve included the full transliteration and the text in Devanagari, both of which I’m wanting to work more with in my practice, to primarily make extensively clear both that my understanding is based on translations and commentary, and to highlight the language and the script as part of the context of yoga’s roots.

योगश्चित्तवृत्तिनिरोधः॥२॥

Yogaścittavṛttinirodhaḥ||2||

The restraint of the modifications of the mind-stuff is Yoga.

तदा द्रष्टुः स्वरूपेऽवस्थानम्॥३॥

Tadā draṣṭuḥ svarūpe’vasthānam||3||

Then the Seer (Self) abides in Its own nature.

वृत्तिसारूप्यमितरत्र॥४॥

Vṛttisārūpyamitaratra||4||

At other times [the Self appears to] assume the forms of the mental modifications.

If you’ve attended many yoga classes or studied the Sutras, you may have well heard these before. Often, I’ve heard 1.2 discussed as this process of quieting the mind. Certainly there is that, which on its own is a heroic feat. I’d like to note that for our purposes of taking on self-leadership, there are other implications. Restraining these modifications is part of the discernment work to recognize (become aware of) the difference between the Self (our true nature) and the modifications our true nature takes on that keeps us from living and experiencing our lives as our Selves.

वृत्तयः पञ्चतय्यः क्लिष्टा अक्लिष्टाः॥५॥

Vṛttayaḥ pañcatayyaḥ kliṣṭā akliṣṭāḥ||5||

There are five kinds of modifications which are either painful or painless.

प्रमाणविपर्ययविकल्पनिद्रास्मृतयः॥६॥

Pramāṇaviparyayavikalpanidrāsmṛtayaḥ||6||

They are right knowledge, misconception, verbal delusion, sleep, and memory.

Right away, it’s pointed out that we can’t tell that we are living from a modified state rather than that of our true nature based on whether we experience something as painful or not. Something can feel pleasant or ‘be good’ and still be a modification from our Self. Things start to get technical here, so it is best for you to read commentaries on sutras 1.7 to 1.12 written by reputable scholars if you want to reflect on these modifications further, but suffice it to say that they neatly describe just about all I can think of as reality: those things that we touch, see, or hold as belief whether they can be validated or not, thoughts and beliefs that stem from words or ideas from ourselves or someone else, beliefs that come from the absence of stimuli (such as that life ends when brain activity ceases, or that nothing happens while you’re sleeping), and the things we believe or hold as real because we have a memory of it.

This is very abstract, so I’ll highlight how these misconceptions have informed what I often confuse to be my Self. I have belief, direct experience, and memory of being romantically attracted to people of various genders, and so at different points in life I’ve identified as bisexual, lesbian, gay, and most recently queer. I have been sure in many phases of life, especially depending upon my recollection of childhood or politicized fears, that these identity labels meant that my afterlife will be full of Hellfire. As such, I’ve taken steps to overcompensate for the ‘evils’ of my worldly positioning, making efforts to be abundantly caring and to do work that helps uplift others.

Being socially read as Black and male has encouraged me to celebrate my social charms, my diplomatic nature, and my ability to be calm and soft-spoken of the rage and anger that were at the forefront of my mind for years. Knowing that, despite first appearances, I’m “not male like you think I am” has also pushed me to protect myself from being in the company of other men, as well as to use pronouns differently. Even as I identify most accurately with a masculinity that fits better under the he/him/his masculine pronoun identity umbrella, I often experience men’s culture to be hostile and try to separate myself from it. I do this both for my safety and those around me.

Socially and in our material world, these things are all true and manifest in different modifications that I make to blend and survive. None of this gets me closer to my true nature though, or helps others get to their true nature. It makes it harder for us to see more clearly that none of these oppressions are our truth, and to understand that working towards that truth is also a critical key to our individual and collective liberation.

This work on self-leadership with yoga then starts with this question of self, and right away the understanding that we need to be gentle with and forgiving of ourselves for confusing these modifications and tricks of oppression as our actual truth. We need to make space for acknowledging that both the things we like and dislike are part of these modifications and stories we’ve been shaped by. We need to allow ourselves to enjoy what we enjoy as a gift of being embodied, which is also a part of our reality, but to be cognizant of what that means and how to find more joy that leads us closer to ourselves rather than away. Finally we have to take responsibility for our power in being able to override the modifications and stories and recognize that this is lifelong practice rather than something that can be attained.

Let’s practice together?